Inspiration lives on

While spending over four decades in any industry, one is bound to cross paths with people who make an impact on your own life. FRANK BEETON recalls three industry figures, who did just that – and so much more.

When asked to write an article for this issue of FOCUS on people, rather than trucks or companies, I gave considerable thought to the selection of my subjects. Having worked in and with the motor industry for more than 45 years, I have certainly met more than my fair share of “interesting” characters, but truly inspirational people have been a lot thinner on the ground.

Nevertheless, the three personalities featured in this article I consider to have had a profound impact on my own attitude and performance. In their presence, I always felt inspired and empowered. Unfortunately, all three have now passed on to higher service, but the fond memories live on.

W. Robert (Bob) Price

I joined General Motors South Africa as truck area manager, in the Durban regional office, in 1978. In early 1980, I was promoted to government sales manager, and transferred to head office in Port Elizabeth. Over the following six years I held virtually every management post in GMSA’s Truck Sales Division, and was heading up the division by 1986.

At that time, there was considerable uncertainty over GM’s future in the country, with frequent rumours of sell-offs and withdrawals. Several times, we looked out of our office window in Kempston Road, to find the directors’ car park completely empty, which set the rumour mill off again at an accelerated pace.

At that time, there was considerable uncertainty over GM’s future in the country, with frequent rumours of sell-offs and withdrawals. Several times, we looked out of our office window in Kempston Road, to find the directors’ car park completely empty, which set the rumour mill off again at an accelerated pace.

This atmosphere was not conducive to good morale in the company, and the management team had shrunk somewhat, requiring some realignment of responsibilities. In this process, I had re-inherited the government sales portfolio, in addition to my other duties.

As 1986 neared its end, however, we were aware that something big was about to break and one morning management were asked to gather in a small theatre situated at the end of the first floor

office corridor. While we were sitting anxiously waiting to discover our fate, the door opened and in walked a tall American. Every person in the room leapt to their feet and broke out in spontaneous applause.

This was, of course, W. Robert Price, who had been GMSA’s managing director from 1971 to 1974, and had led the company through some of its most successful years in the country (he had subsequently moved on to head up Vauxhall Motors in the United Kingdom, and GM’s Motors Trading Corporation).

During the meeting, we were told about the unfolding developments that would lead to the establishment of the Delta Motor Corporation, and that Price had resigned from GM and would be our chief executive. This was the best possible news for the somewhat dispirited management team (many of whom firmly believed that Price could walk on water), and helped greatly to ensure that key personnel stayed with the company.

During the following year, I got to know Price well. With the impending change in corporate identity, it was important to retain our hard-won government supply contracts through the changeover, and I was responsible for taking Price to meet senior personnel in the departments that were our important customers. His charisma was put to work, and their reaction to the “localisation” of GMSA was almost as enthusiastic as that of the company’s management, so everything went off smoothly.

However, I soon also discovered that Price also had a substantial personal interest in the truck business, and he identified Tony Barlow and me as the “truck guys” in the company. The three of us held many long discussions on our future business direction, in the Johannesburg regional office boardroom, after our day’s work was completed.

In his final years at GM, Price had spent some time in Europe trying to find a suitable partner for the Corporation’s global truck business, and he soon began the process of calling meetings between ourselves and potential local partners.

Alas, much of this vision came to naught; Price passed away, very unexpectedly, from a heart attack on Saturday, October 10, 1987 – aged only 61. He did, however, live long enough to see the formal launch of Delta Motor Corporation early in that year, and to witness the early stages of its success.

His vision for an expanded truck business did not materialise, however, and Delta retained the same level of partial participation in the market that had prevailed at the end of the GM era, until it was re-acquired by the American corporation in 2004.

By the end of 1988, I had become frustrated by the lack of progress of the company and the indecision over my own career path, and so moved on to other challenges. Price had certainly left a lasting impression on me, however, and I have no doubt that, had he lived longer, I would have been happy to stay and support his ambitions for a more comprehensive Delta presence in the truck business.

Makoto Hisano

I first visited Japan in 1985, co-hosting a press contingent on behalf of General Motors (GM). By then, I had had frequent dealings with Japanese representatives from Isuzu Motors, and, to a lesser extent, Suzuki (my tender sales staff were also responsible for controlling the importation programme for Suzuki vehicles).

On that trip, we visited the Isuzu operations at Kawasaki (since closed), Fujisawa, Tomakomai – the impressive test facility on the northernmost island of Hokkaido – as well as Suzuki’s ultra-modern plant at Hamamatsu.

On that trip, we visited the Isuzu operations at Kawasaki (since closed), Fujisawa, Tomakomai – the impressive test facility on the northernmost island of Hokkaido – as well as Suzuki’s ultra-modern plant at Hamamatsu.

When I joined Nissan South Africa’s (NSA’s) truck division in 1990, initially as national fleet sales manager, I soon renewed my acquaintance with Japanese culture, which was, understandably, even more of an influence at NSA than at GMSA; which had retained a substantial American flavour.

Following a reshuffle in the miniscule Nissan truck division, I was given responsibility for the product management function, which involved considerably more interface with the local and visiting Nissan Diesel (ND) personnel.

To be honest, my initial impressions of the former were less than favourable, as the incumbents appeared to be unwilling or unable, to sufficiently advance Nissan South Africa’s interests with their overseas colleagues.

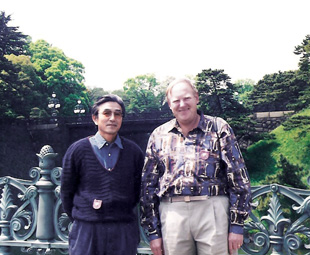

I then met one Makoto Hisano, a general manager in the export department, on one of my subsequent Japanese trips, and decided that he was someone with whom I could really do business.

I need to explain that the timeframe was particularly critical to ND’s business in South Africa. We were about to shake off the yoke of Atlantis Diesel Engines (ADE) and other obligatory local content, and revert to original equipment drivelines.

We had already taken the lead among local manufacturers by breaking the ADE mould with the original Nissan Diesel Cabstar, but with a gross vehicle mass (GVM) rating of only six tonnes, this model was not able to exploit the most important nominal four-tonne payload niche in the medium commercial vehicle segment.

We desperately needed a seven-tonne GVM model to take on the equivalent Toyota Dyna and Isuzu N4000D trucks (the latter being a product of my own earlier product planning efforts at GMSA/Delta), as this would give NSA an immediate and significant benefit in truck market penetration.

It seemed that Nissan Diesel had absolutely the right product in its ZZ light truck series. Powered by a large 4,6-litre, naturally-aspirated four-cylinder diesel, with GVM ratings of up to seven tonnes, it looked spot-on for South African conditions, but it soon emerged that some obstacles needed to be overcome.

First, that range had been less than successful in the domestic Japanese market, and ND was aiming to discontinue it largely in favour of bought-in products from Isuzu.

Second, the name “Nissan Diesel Cabstar”, which we intended to continue on the ZZ Series, cut straight across the naming rights of Nissan Motor Company, that owned, and intended to jealously guard, the Cabstar brand. Our earlier use of this combination of names on the six-tonne GVM model had apparently severely ruffled some Japanese feathers!

At around the time that these issues were presenting as serious obstacles to our MCV aspirations, we had an enormous stroke of good fortune, in that Hisano-san was posted to South Africa as ND’s resident representative.

This was quite unexpected, as his position within ND, as a general manager, was above that of previous locally-based staff. However, this was an inspirational move by ND, and proved a godsend in the (sometimes extremely tense) negotiation process that followed. NSA duly got its Nissan Diesel Cabstar 35 and 40 range, which turned out to be an unbridled success.

My personal relationship with Hisano-san was one of the highlights of my ten-year stay at ND. I had the honour of visiting his house in Japan, and meeting his charming wife, who had elected to remain at home while he completed his South African assignment. He nursed me through one Japanese trip when I contracted a nasty bout of influenza, feeding me various potions of dubious origin, but which certainly worked.

My personal relationship with Hisano-san was one of the highlights of my ten-year stay at ND. I had the honour of visiting his house in Japan, and meeting his charming wife, who had elected to remain at home while he completed his South African assignment. He nursed me through one Japanese trip when I contracted a nasty bout of influenza, feeding me various potions of dubious origin, but which certainly worked.

He would often come into my office in Sandton to discuss corporate politics in hushed tones, and obviously appreciated my gai-jin (foreigner’s) perspectives, explanations and insights. He was a man of great dignity and integrity, and elevated my opinion of his countrymen to new heights.

My favourite Hisano-san story involves a practical joke I once played on him. During my first visit to Japan in 1985, I had been given some Japanese calling cards to use on the trip. These contained my name written in Japanese, and I kept a few of them for possible future reference.

One day, back in South Africa, I carefully copied the Japanese version of my name, freehand, on to a piece of note paper, took it to him, and asked: “Hisano-san, can you translate this please?”

He looked at it in total astonishment, and demanded “How did you do that?” We both fell about laughing when I explained, and he was able to relax in the knowledge that I had not suddenly become literate in his home language. (We had long since realised that Japanese managers like being able to converse confidentially with their colleagues in their own language when negotiating with foreigners. South Africans usually retaliated by speaking Afrikaans to each other!)

Hisano-san duly finished his local assignment, and moved on to head up Nissan Diesel’s bus and coach-building joint venture with Jonckheere in the Phillipines. I was greatly saddened to hear that he had subsequently passed away while still there, under somewhat unusual circumstances, in 2002, aged only 58. I will certainly always remember him as a perfect gentleman, a highly valued colleague, and a good friend.

Tony Twine

The third inspirational person on my personal list is the inimitable Tony Twine. I first encountered Tony in 1984 when I was working for General Motors. He had been asked by ADE to bring some sanity to the forecasting process related to the South African truck market. ADE was receiving advance indents from individual manufacturers totalling well in excess of 100 percent of the actual demand, and this was playing havoc with inventories and forward indents.

Twine, in typically efficient fashion, soon created a rational model based on macro-economic inputs that has remained the industry standard up until this day. This process enabled him to regularly participate in Max Braun’s “Outlook for Trucks” conferences, and to be retained for management consultations by many of the local truck manufacturers. I attended a number of his presentations during my stints at GM and NSA.

Then, in 2001, after I had left the formal motor industry, it was Twine, who by that time had become a director and senior economist at Econometrix, who provided me with the opportunity to base my fledgling consultancy activities within the organisation.

Then, in 2001, after I had left the formal motor industry, it was Twine, who by that time had become a director and senior economist at Econometrix, who provided me with the opportunity to base my fledgling consultancy activities within the organisation.

The valuable credibility that came with the association, as well as the administrative support that enabled me to concentrate fully on enjoying the work, have enabled me to spend the past fourteen years as a strategic analyst of, and commentator on, the local commercial vehicle industry – and for that I am extremely grateful.

But what of Tony Twine, the man? By the time I met him, he had already lost most of his eyesight due to his diabetic condition, but far from becoming disheartened by this very significant impairment, it seemed that he was spurred on to greater achievements. During the eleven years of our close working relationship, I often marvelled at the way that he coped in an environment that required copious interaction with reams of facts and data.

He had an amazing memory for detail, and could direct his sighted colleagues to the exact cell in a specific Excel workbook where a required value was to be found. I found this a touch intimidating at first, but later realised that it was just the way that his brain worked, and was more than happy to accept the functional benefits.

Twine had an infectious sense of humour, and enjoyed bouts of verbal sparring over words that sometimes left me a little dizzy. He had a substantial command of the English language, and loved to use obscure witticisms that he found extremely amusing. This often came out in his prolific writing.

He was incredibly tolerant of the media, even when they asked him questions at the most inconvenient of times, and always went to great lengths to explain advanced economic theory in terms that everybody, including the lay public, could readily understand.

Twine was also not above laughing at himself. I once accompanied him to a presentation at a well-known Magaliesberg venue. The audience was configured in one of those “hollow-square” formations, and Tony and I ended up seated on one of the corners, adjacent to a doorway. When he got up to speak, he pushed back his chair, and with a low table in front, he had no tactile reference to his position relative to the audience.

By the end of the presentation, he had “drifted” half way out of the doorway, and was addressing the adjacent empty room! This provided us all with a good laugh, but after that we always made sure that he had a lectern, or some other piece of furniture, to which he could anchor himself during his presentations.

It is still very hard to believe that he is no longer with us, but the huge number of tributes, emanating from prominent dignitaries and the most humble of people, that poured in after March 11, 2012, bear testament to the rich legacy that he has left behind. To put it in a nutshell, Tony Twine may have been small in stature, but he was a giant in intellect.

Published by

Focus on Transport

focusmagsa