Today’s technology, tomorrow’s engines

GAVIN MYERS delves into drivetrain technology predictions to uncover the power behind vehicles of the future

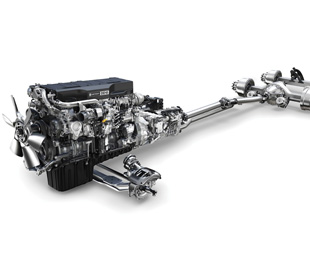

For more than a century the internal combustion engine (ICE) has been the powertrain of choice for the world’s road-based vehicles, but what might become of it in future?

Governments the world over continually implement ever stricter emissions legislation and incentivise the use of electric vehicles – especially in city centres where pollution has become a touchy subject – while engine manufacturers endeavour to advance the development of powertrains running on alternative fuels, to the ire of the world’s oil companies.

It’s a sticky situation that places all ICE-powered vehicles at the centre of a tug-of-war between global warming, technological advancement, political points and profits.

In 2016, the European Road Transport Research Advisory Council (ERTRAC) published its 75-page report entitled: Future Light and Heavy Duty ICE Powertrain Technologies.

Covering all topics from the current European scenario to ICE technologies and the role of transmissions, the report makes for some interesting reading and could provide some clues as to the future of the ICE.

From ERTRAC’s perspective, fossil-based fuels are expected to continue to dominate the energy pool for road transport until 2030, and, over an even longer period (2040+) the road-transport energy supply mix will be composed of four main parts: oil-based fuels, natural gas, renewable liquid fuels and electricity (produced mainly from renewables).

The heavy-duty vehicle market is expected to be dominated by the ICE until at least 2050; given the need for power and energy density for the propulsion of these vehicles (which is provided by liquid and gaseous fuels) and the widespread existing infrastructure.

“The energy density of chemical energy storage in hydrocarbon-based fuel, and, thus, the vehicle’s range, will always be greater than that provided by electro-chemical storage,” the report states.

With that in mind, the question is raised of how the ICE (in this case referring specifically to diesel) can be continually improved over the next 30-or-so years.

According to the report, the higher cost of diesel technology relative to petrol is primarily attributable to the cost of the combustion system technology (air handling, fuel injection, higher-pressure engine operation) and emission-control equipment. Overcoming the barriers will help maximise fuel economy, improve exhaust after-treatment system effectiveness and durability and reduce overall costs.

This will be even more pertinent when one considers that the European Union (EU) Climate and Energy Framework has stated an objective of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the EU from by 80 to 95 percent, by 2050, compared with 1990 levels.

This will be even more pertinent when one considers that the European Union (EU) Climate and Energy Framework has stated an objective of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the EU from by 80 to 95 percent, by 2050, compared with 1990 levels.

The Transport White Paper, issued in 2011, states a specific transport-sector objective to reduce the GHG emissions by 60 percent by 2050 compared to 1990, and by 20 percent by 2030 compared to 2008 levels.

For the heavy-duty sector, the realisation of the EU GHG targets for 2050 will require a yearly reduction of CO2 of at least three percent across the complete annual new heavy-duty vehicle fleet sales in the EU. To do so will require massive effort and increasing the efficiency of powertrains will be the name of the game.

So, how to improve the ICE and powertrain? ERTRAC quotes three steps:

1. Improving engine efficiency, particularly with regard to the properties of low-carbon fuels;

2. The use of low-carbon/near net-zero carbon fuels;

3. Electrification, including hybridisation (which requires highly efficient and ultra-clean ICEs that use renewable, low-carbon fuels).

Considering the inefficiencies of modern ICE powertrains (which the report elaborates on extensively), overall efficiency improvements of between ten and 12 percent can be realised with compression-ignition engines (and about 15 percent for spark-ignition engines). How can this be achieved?

“Increasing ICE thermal efficiency and reducing heat and friction losses still represent important fields to recover and save energy. The role and use of advanced materials should not be underestimated here,” the report notes.

“A specific pathway to a significant increase of powertrain efficiency lies in an unbiased reallocation of powertrain functions and redesign of powertrain architecture,” the report adds.

Furthermore, when one considers that 70 percent of the combustion energy is converted to heat that is lost through the exhaust and cooling systems, the re-use of waste heat represents a great opportunity to improve the efficiency of the internal combustion engine. This is especially true in high-load operation and heavy-duty vehicle applications.

While many of these considerations are expected to occur during the heavy-duty vehicle evolution and/or as part of heavy-duty powertrain hybridisation, the load operation for the heavy-duty engine and its performance and efficiency will become more challenging.

“Efficiency measures are simply not sufficient,” ERTRAC says. “In addition, understanding the impacts of emerging fuel changes (for example, biofuels) is critical and a large-scale introduction of alternative fuels is also necessary to accomplish a reduction of GHG emissions of the required magnitude.”

To make this possible, diesel fuel will also need to evolve to third-generation biodiesel, in order to overcome current limitations in blending biodiesel in modern diesel engines.

“Current emission-reducing trends – in increasing the pressure of injection systems and the complexity of the after-treatment system, together with the durability requirement – demand bio/renewable diesel fuels that could be produced from vegetable oils, waste oils, sugars and biomass, using processes such as hydro treating (HVO), hydrogenation, sugar-to-diesel and Fischer-Tropsch (FT), for example.

“In parallel with ‘conventional’ advanced biodiesel fuels, new processes for sustainable bio-methanol production will also pave the way for a wider use of Dimethyl-Ether (DME – a synthetically produced alternative to diesel for use in specially designed compression-ignition engines) as well as, on the engine combustion side, advanced concepts for dual-fuel approaches.

“This could provide the solution to maintain diesel engine efficiency while introducing different kinds of alternative fuels. Looking further into the future, work is being done to explore the use of algae to produce liquid as well as gaseous biofuels,” the report states.

Despite this article not looking at transmission and other driveline components as discussed in the report, it’s clear that there is much to be considered if future GHG targets are to be met. In addition, the report suggests that vehicle aerodynamics, rolling resistance, optimised vehicle loading and diversity of vehicle operation need to be improved.

“The redesign requires novel transmissions and breaks with the off-the-shelf recombination of existing modules from non-hybrid powertrains into a hybrid powertrain. On the other hand, it offers the chance to provide full powertrain functionality at reduced complexity and cost. The latter is of paramount importance for customer acceptance and fast market penetration of electrified powertrains,” ERTRAC says.

“All improvements in the ICE technology will have significant beneficial impacts on fuel consumption, on people and goods transport efficiency, on CO2 output and on emissions reduction, with a wider use of low-carbon fuels (such as natural gas) and renewable fuels (advanced liquid biofuels and bio and synthetic methane), over a long period of time.

“These improvements, when integrated with the electrification of vehicles in the form of hybridisation, will maximise impact at the lowest cost,” says ERTRAC.

Here’s looking forward to 30 more years of interesting ICE development.

Published by

Focus on Transport

focusmagsa

FUSO: Driving the Future of Mobile Healthc

FUSO: Driving the Future of Mobile Healthc

New Electric Van Range Unveiled!

New Electric Van Range Unveiled!  A brand

A brand

Wondering about the maximum legal load for a

Wondering about the maximum legal load for a

The MAN hTGX powered by a hydrogen combus

The MAN hTGX powered by a hydrogen combus

Exciting News for South African Operators

Exciting News for South African Operators